Andrej Karpathy describes the current moment as the rise of a new computing paradigm that he calls Software 3.0. as large language models emerge not just as clever chatbots but as a “new kind of computer” (“LLM OS”). In this model, the LLM is the processor, its context window is the RAM, and a suite of integrated tools are the peripherals. We program this new machine not with rigid code, but with intent, expressed in plain language. This vision is more than a technical curiosity; it is a glimpse into a future where our systems don’t just execute commands, but understand intent.

Healthcare is the perfect test bed for this paradigm. For decades, the story of modern medicine has been a paradox: we are drowning in data, yet starved for wisdom. The most vital clinical information—the physician’s reasoning, the patient’s narrative, the subtle context that separates a routine symptom from a looming crisis—is often trapped in the dark matter of unstructured data. An estimated 80% of all health data lives in notes, discharge summaries, pathology reports, and patient messages. This is the data that tells us not just what happened, but why.

For years, this narrative goldmine has been largely inaccessible to computers. The only way to extract its value was through the slow, expensive, and error-prone process of manual chart review, or a “scavenger hunt” through the patient chart. What changes now is that the new computer can finally read the story. An LLM can parse temporality, nuance, and jargon, turning long notes into concise, cited summaries and spotting patterns across documents no human could assemble in time.

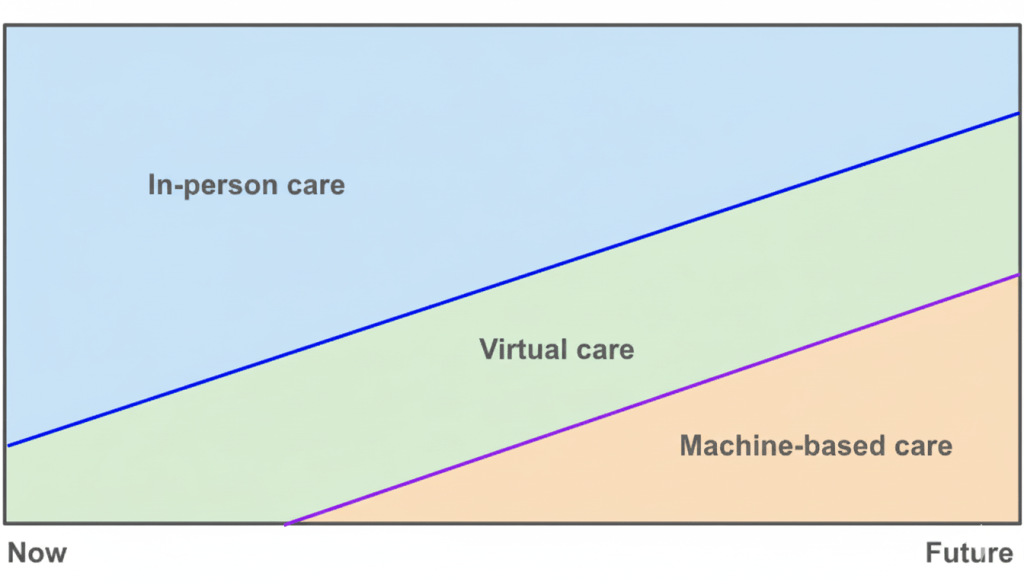

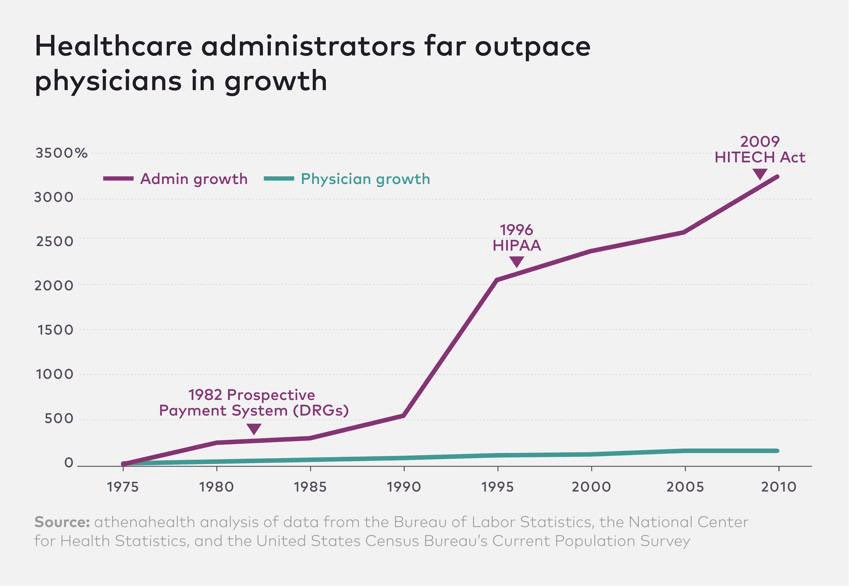

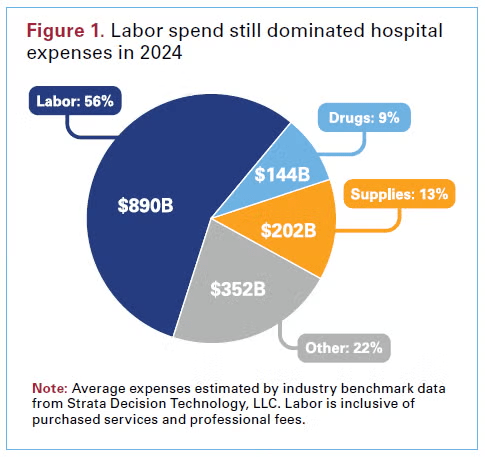

But this reveals the central conflict of digital medicine. The “point-and-click” paradigm of the EHR, while a primary driver of burnout, wasn’t built merely for billing. It was a necessary, high-friction compromise. Clinical safety, quality reporting, and large-scale research depend on the deterministic, computable, and unambiguous nature of structured data. You need a discrete lab value to fire a kidney function alert. You need a specific ICD-10 code to find a patient for a clinical trial. The EHR forced clinicians to choose: either practice the art of medicine in the free-text narrative (which the computer couldn’t read) or serve as a data entry clerk for the science of medicine in the structured fields. Often, the choice has been the latter, which has contributed to massive burnout among physicians. This false dichotomy has defined the limits of healthcare IT for a generation.

The LLM, by itself, cannot solve this. As Karpathy points out, this new “computer” is deeply flawed. Its processor has a “jagged” intelligence profile—simultaneously “superhuman” at synthesis and “subhuman” at simple, deterministic tasks. More critically, it is probabilistic and prone to hallucination, making it unfit to operate unguarded in a high-stakes clinical environment. This is why we need what Karpathy calls an “LLM Operating System”. This OS is the architectural “scaffolding” designed to manage the flawed, probabilistic processor. It is a cognitive layer that wraps the LLM “brain” in a robust set of policy guardrails, connecting it to a library of secure, deterministic “peripheral” tools. And this new computer is fully under the control of the clinician who “programs” it in plain language.

This new architecture is what finally resolves the art/science conflict. It allows the clinician to return to their natural state: telling the patient’s story.

To see this in action, imagine the system reading a physician’s note: “Patient seems anxious about starting insulin therapy and mentioned difficulty with affording supplies.” The LLM “brain” reads this unstructured intent. The OS “policy layer” then takes over, translating this probabilistic insight into deterministic actions. It uses its “peripherals”—its secure APIs—to execute a series of discrete tasks: it queues a nursing call for insulin education, sends a referral to a social worker, and suggests adding a structured ‘Z-code’ for financial insecurity to the patient’s problem list. The art of the narrative is now seamlessly converted into the computable, structured science needed for billing, quality metrics, and future decision support.

This hybrid architecture—a probabilistic mind guiding a deterministic body—is the key. It bridges the gap between the LLM’s reasoning and the high-stakes world of clinical action. It requires a healthcare-native data platform to feed the LLM reliable context and a robust system of action layer to ensure its outputs are safe. This design directly addresses what Karpathy calls the “spectrum of autonomy.” Rather than an all-or-nothing “agent,” the OS allows for a tunable “autonomy slider.” In a “co-pilot” setting, the OS can be set to only summarize, draft, and suggest, with a human clinician required for all approvals. In a more autonomous “agent” setting, the OS could be permitted to independently handle low-risk, predefined tasks, like queuing a routine follow-up.

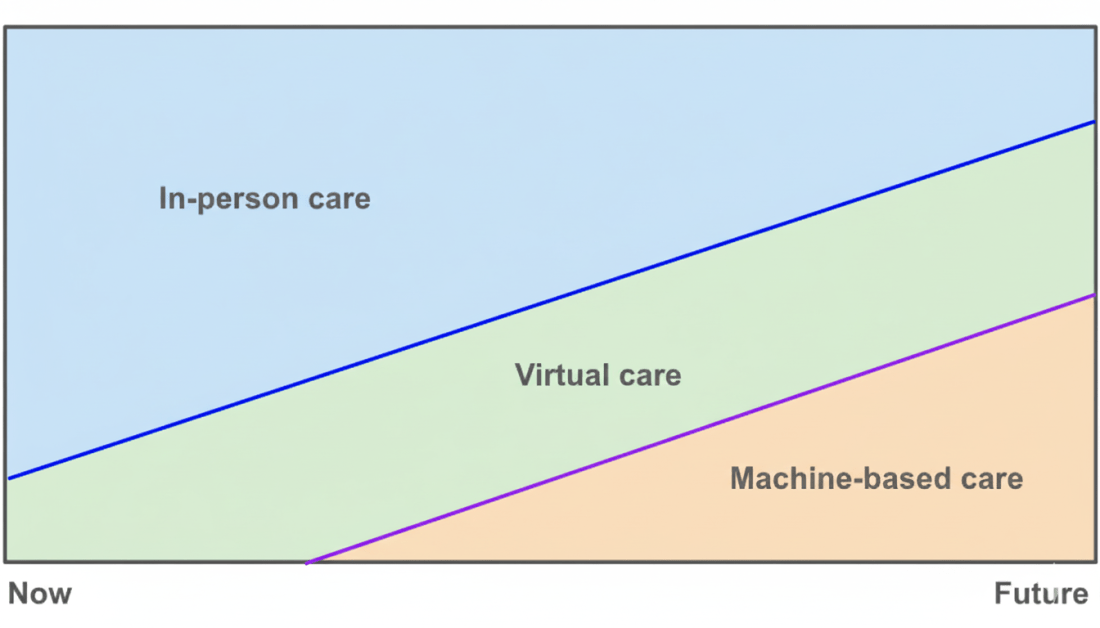

The journey is just beginning in healthcare, and my guess is that we will see different starting points for this across the ecosystem. But the path forward is illuminated by a clear thesis: the “new computer” for healthcare changes the very unit of clinical work. We are moving from a paradigm of clicks and codes—where the human serves the machine—to one of intent and oversight. The clinician’s job is no longer data entry. It is to practice the art of medicine, state their intent, and supervise an intelligent system that, for the first time, can finally understand the story.