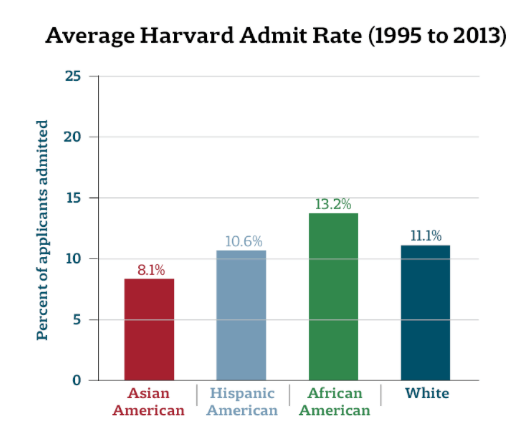

The recent Supreme Court decision on affirmative action strikes home in a deeply personal way. As a second-generation Korean American who attended Harvard College in the late 1990s, I always considered myself very lucky. Our family had no connections to Harvard, or any other college for that matter, and I was not a recruited athlete. Asian Americans were 16% of the admitted class when I went to school and had the lowest rate of acceptance among all ethnicities. At the time, it felt like a miracle to hear that I had been accepted to Harvard. Little did I know that the statistical odds were very much stacked against applicants like me.

I find the Asian American point of view to be mostly missing in the Supreme Court’s decision and the broader media coverage. In particular, the outright racism that Harvard and a number of other schools built into their admissions process for Asian students is glossed over despite how blatantly it disadvantaged Asian candidates.

In the various criteria that Harvard used for admissions, Asian American candidates rated lowest on “personal” criteria for “likability, courage, and kindness” compared to white applicants. The penalty that Asian American candidates faced for simply being Asian is a big reason why Asian parents and students for years have tried to underplay their “Asian-ness”. My parents suspected that my brothers and I had to be better than similarly situated candidates to overcome this penalty, and my guess is this is why many Asian parents push their children so hard.

Despite prior case law dictating that race could only be used as a “positive” when it came to college admissions and not as a “negative,” being Asian American was most certainly a negative for many candidates.

The systemic underrating of Asian American applicants based on personal character assessments is a reflection of systemic bias and stereotypes at Harvard, even to the point of jokes between the head of admissions at Harvard and a government regulator referencing Asian stereotypes. How often in the admissions process were Asian American students characterized as quiet, studious, good at math, destined for medical school?

As one Harvard admissions officer noted in an Asian American applicant’s file: “quiet and of course wants to be a doctor.”

While affirmative action is most often defended in the context of systemic wrongs like slavery and segregation, the history of Asian exclusion in America cannot be ignored. From the first Chinese immigrants to the United States and the Japanese internment, Asian Americans have always been considered separate from the mainstream, a lower class of “other” people who could never be assimilated. The current wave of violence against Asian Americans is just the latest in a long history of racism against Asian Americans in this country.

As the Court noted, college admissions is a zero-sum game — there are only a fixed number of slots for a plethora of qualified candidates. Is there a “fair” way to allocate these slots?

The answer to this question depends on your point of view on the role of higher education and what the stakes are.

I have always viewed education primarily as a means to an end — a pathway to the workforce in particular. For many professions, college is one of many filters (along with your GPA, SAT score, MCAT, LSAT, etc). The bigger picture stakes are really about which higher-paying jobs are accessible to younger people as they grow into the workforce and ultimately how we address our yawning income inequality gap.

The good news is that colleges have lost their monopoly as a filter to success, and there are many alternative pathways to higher-earning jobs than going to a traditional four-year school. That said, there are still many “traditional” pathways where the college is still a gatekeeper to future opportunities.

One could argue — as I am now — that the diversity interest that colleges should serve is less to ensure a “racially diverse student body” for educational benefits, which the Court struck down here, and more about playing a role to ensure that we have a society that levels the playing field for those who have the ability and yet currently lack the economic means.

One of the more striking statistics to emerge from the Harvard case is the wealth distribution of students and their families. In this study, Professor Chetty found that 67% of Harvard undergraduates come from the top 20% of the income distribution while just 4.5% come from the bottom 20%.

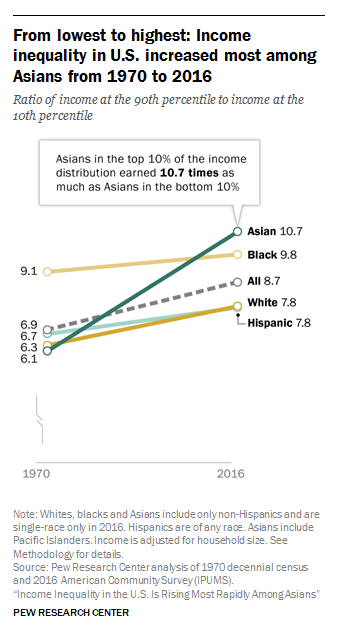

In the wake of the Supreme Court case striking down affirmative action, I believe a class-based, “race-neutral” admissions system would help Asian Americans.

Asian Americans have had the fastest-growing income inequality among all racial and ethnic groups.

When you explode the earnings power of Asian American groups, the income inequality is striking and this is what we should collectively work to address.

The most recent class at Harvard has admitted the most Asian Americans ever — now almost 30% of the class, which is nearly double the rate when I went to school. My hope is that more of these admits are students who never thought they would have a chance without the privilege of a wealthier family background. My longer-term bet is that colleges like Harvard will need to address the tricky subject of legacy admissions as it is an undeniable counterweight to efforts to balance the class.

There is a bigger battle ahead with workplace diversity and how we ensure that opportunities for underrepresented groups continue to remain viable despite the changes upstream in higher education. My hope is that higher education institutions will find a way to continue to be viable sources of diverse talent.