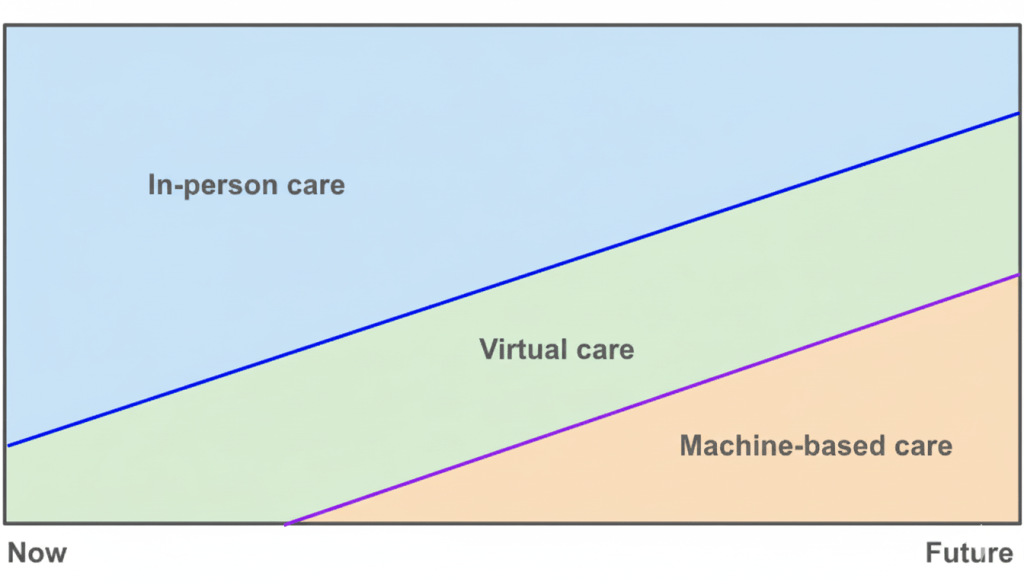

Almost ten years ago at Apple, we had a vision of how care delivery would evolve: face‑to‑face visits would not disappear, virtual visits would grow, and a new layer of machine-based care would rise underneath. Credit goes to Yoky Matsuoka for sketching this picture. Ten years later, I believe AI will materialize this vision because of its impact on the unit economics of healthcare.

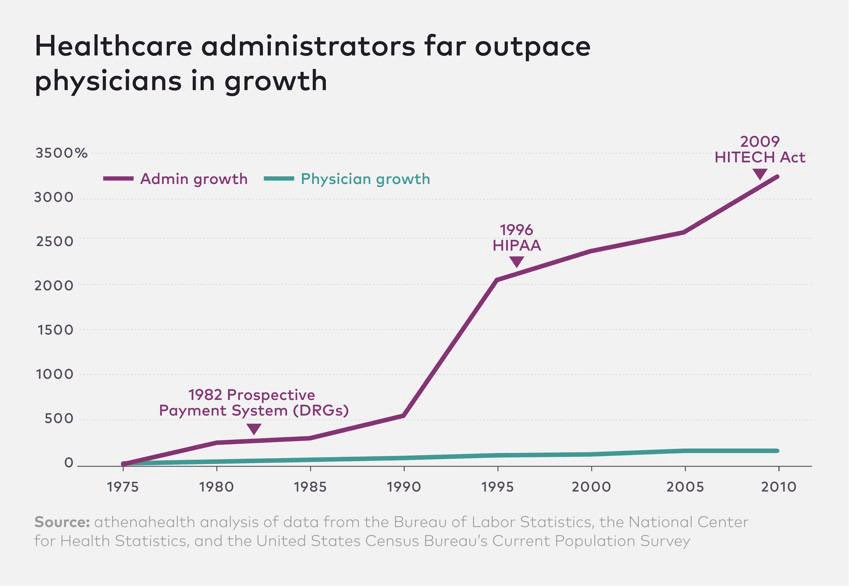

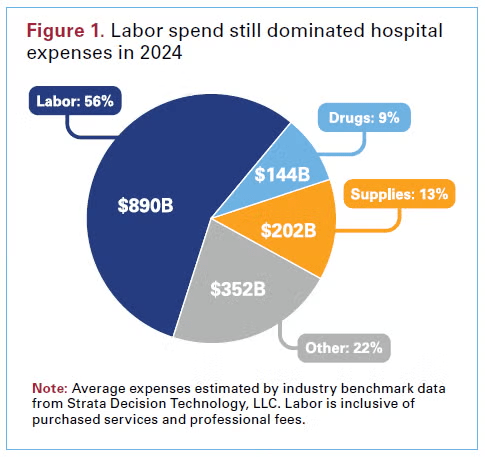

Labor is the scarcest input in healthcare and one of the largest line items of our national GDP. Administrative costs continue to skyrocket, and the supply of clinicians is fixed in the short run while the population ages and disease prevalence grows. This administrative overhead and demand-supply imbalance are why our healthcare costs continue to outpace GDP.

AI agents will earn their keep when they create a labor dividend, either by removing administrative work that never should have required a person, or by letting each scarce clinician produce more, with higher accuracy and fewer repeats. Everything else is noise.

Administrative work is the first seam. Much of what consumes resources is coordination, documentation, eligibility, prior authorization, scheduling, intake, follow up, and revenue cycle clean up. Agents can sit in these flows and do them end to end or get them to 95 percent complete so a human can finish. When these agents are priced in ways where the ROI is attributable, I believe adoption will be rapid. If they replace a funded cost like scribes or outsourced call volume, the savings are visible.

Clinical work is the second seam. Scarcity here is about decisions, time with the patient, and safe coverage between visits. Assistive agents raise the ceiling on what one clinician can oversee. A nurse can manage a larger panel because the agent monitors, drafts outreach, and flags only real exceptions. A physician can close charts accurately in the room and move to the next patient without sacrificing documentation quality. The through line is that assistive AI either makes humans faster at producing billable outputs or more accurate at the same outputs so there is less rework and fewer denials.

Autonomy is the step change. When an agent can deliver a clinical result on its own and be reimbursed for that result, the marginal labor cost per unit is close to zero. The variable cost becomes compute, light supervision, and escalation on exceptions. That is why early autonomous services, from point‑of‑care eye screening to image‑derived cardiac analytics, changed adoption curves once payment was recognized. Now extend that logic to frontline “AI doctors.” A triage agent that safely routes patients to the right setting, a diagnostic agent that evaluates strep or UTI and issues a report under protocol, a software‑led monitoring agent that handles routine months and brings humans in only for outliers. If these services are priced and paid as services, capacity becomes elastic and access expands without hiring in lockstep. That is the labor dividend, not a marginal time savings but a different production function.

I’m on the fence about voice assistants, to be honest. Many vendors claim large productivity gains, and in some settings those minutes convert into more booked and kept visits. In others they do not and the surplus goes to well-deserved clinician well‑being. That is worthwhile, but it can also be fragile when budgets compress. Preference‑led adoption by clinicians can carry a launch (as it has in certain categories like surgical robots), but can it scale? Durable scale usually needs either a cost it replaces, a revenue it raises, or a risk it reduces that a customer will underwrite.

All of this runs headlong into how we pay for care. Our reimbursement codes and RVU tables were built to value human work. They measure minutes, effort, and complexity, then translate that into dollars. That logic breaks when software does the work. It also creates perverse outcomes. Remote patient monitoring is a cautionary tale that I learned firsthand about at Carbon Health. By tying payment to device days and documented staff minutes with a live call, the rules locked in labor and hardware costs. Software could streamline the work and improve compliance, but it could not be credited with reducing unit cost because the payment was pegged to inputs rather than results. We should not repeat that mistake with AI agents that can safely do more.

With AI agents coming to market over the next several years, we should liberalize billing away from human‑labor constructs and toward AI‑first pricing models that pay for outputs. When an agent is autonomous, I think we should treat it like a diagnostic or therapeutic service. FDA authorization should be the clinical bar for safety and effectiveness. Payment should then be set on value, not on displaced minutes. Value means the accuracy of the result, the change in decisions it causes, the access it creates where clinicians are scarce, and the credible substitution of something slower or more expensive.

There is a natural end state where these payment models get more straightforward. I believe these AI agents will ultimately thrive in global value‑based models. Agents that keep panels healthy, surface risk early, and route patients to the moments that matter will be valuable as they demonstrably lower cost and improve outcomes. Autonomy will be rewarded because it is paid for the result, not the minutes. Assistive will thrive when it helps providers deliver those results with speed and precision.

Much of the public debate fixates on AI taking jobs. In healthcare it should be a tale of two cities. We need AI to erase low‑value overhead, eligibility chases, prior auth ping pong, documentation drudgery, so the scarce time of nurses, physicians, and pharmacists stretches further. We need to augment the people we cannot hire fast enough. Whether that future arrives quickly will be decided by how we choose to pay for it.