Some personal opinions on what DOGE and #MakeAmericaHealthyAgain could do to reshape U.S. healthcare.

The HHS budget is ~$1.8 trillion, ~23% of the federal budget as proposed for FY25; CMS makes up the lion’s share of the budget (>80%). Hard to imagine reducing the deficit without major changes in how healthcare is funded and delivered.

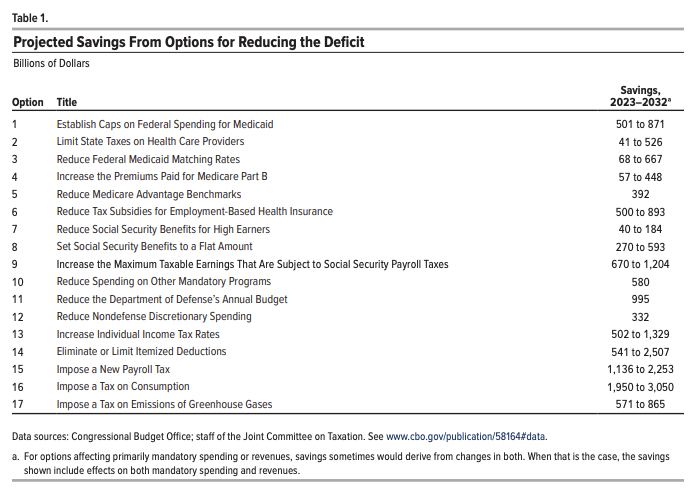

In this table from the Dec 2022 OMB analysis of options to reduce the deficit, it is notable that most of the options involve cuts to Medicare and Medicaid.

Beyond these kinds of cuts, resetting the market dynamics and incentives of all players in the system, including individuals, could improve health outcomes in the long run.

Insurance and consumer-driven healthcare. One of the original sins of our healthcare system is the tax subsidy for employer-sponsored health insurance (IRC § 106). This preferential tax treatment is a major distortion of the market, bifurcating the buyers and consumers of healthcare and encouraging overconsumption.

It is also one of the federal government’s largest tax expenditures: $641 Bn in 2032.

The alternative would be to decouple employment from health insurance and give people more choice, accountability, and portability for how they get healthcare. Dr. Oz has written about shifting towards a Medicare Advantage (MA) for All system where employers fund a 20% payroll tax with a 10% individual income tax to extend the MA program to all Americans not on Medicaid. These dollars could be pooled into an expanded set of tax-advantaged individual & family accounts that could be used to buy insurance, similar in concept to Singapore’s healthcare system.

MA has grown in popularity with >50% of eligible beneficiaries opting for it over the traditional program, and it is one of the few pockets of our healthcare system that operates on the basis of consumer choice, where payers have a long-term incentive to keep their members healthy, and where value-based care arrangements with providers are common. This is the opposite of commercial insurance, where consumers have few choices beyond those picked for them, where employers-as-payers have little long-term incentive given the short tenure of most employees, and where fee-for-service arrangements are common.

If MA were to become a default option for most Americans, it would need to come with further reform as outlined in the OMB recommendations to become more efficient (e.g., reducing MA benchmarks, increasing Part B premiums) along with other initiatives to standardize processes and reduce administrative waste.

The other option would be to expand ICHRA (which came about during the first Trump administration) by preserving the tax favorability of providing a monthly allowance for employees to purchase individual health insurance while removing the tax subsidy for traditional employer-sponsored health insurance.

In both cases of MA for All or an ICHRA expansion, there would be a greater emphasis on choice, increased portability of plan, and greater accountability on and ownership of the individual for their health, with the biggest differences in the provider networks and how the plans are purchased and administered. The more disruptive move would be to make a cleaner break from employer-administered and sponsored healthcare. I would put my bet on MA for All given its greater scale and maturity compared to ICHRA/ACA.

Providers. The U.S. healthcare provider market is not one market but dozens of local oligopolistic health systems that have enormous pricing power. This market dominance has been compounded by the likes of large insurers that have vertically integrated to acquire provider networks. With the price transparency data that has only recently emerged, it is pretty eye-popping to see that the price dispersion for the same exact service between a large dominant health system and a smaller provider in a local market can be upwards of 300-500%.

The source of market power comes from being the only game(s) in town with respect to inpatient care — hospitals require large pools of capital and certificate-of-need laws are considerable barriers to entry. The prior Trump administration advocating for repealing CON laws could be re-raised in this go-around.

Site neutral payment policies can help neutralize the market advantage and pricing power of incumbents, reducing the pricing arbitrage that directs patients currently to higher-cost care settings.

Provider capacity needs to be expanded and liberalized to serve a better-functioning marketplace. The byzantine rules and regulations of state licensure authorities unnecessarily restrict provider entry and ability to practice, in particular for allied health professionals. The inane process for provider enrollment and credentialing restricts the labor market by delaying the process for onboarding a new provider into a practice by months.

Telemedicine and digital health more broadly need to be woven into the fabric of the broader provider marketplace rather than force-fit into the antiquated rules of traditional brick-and-mortar care to maximize available provider capacity. Patients should be able to establish care with telemedicine providers without needing to be seen in person first. Telehealth providers should be able to provide care for patients wherever they might be. And reimbursement for digital health and telemedicine should be at parity to traditional care. With AI-driven care models on the horizon, payment models should incentivize the utilization of these technologies to increase access and reduce the cost of care.

Empowering consumers. Even with the changes above, a consumer-driven healthcare system won’t be possible without greater price transparency and data liquidity. The existence of Costplusdrugs or GoodRx show the demand for transparent pricing models, and despite the push for greater transparency of hospital prices, many hospitals are not compliant and the average consumer has no chance of looking up prices on their own. Portability of one’s own data and giving consumers greater control of their own medical data has been a long-term goal of the federal government and was a Trump-45 era initiative that should be revived: https://cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-announces-myhealthedata-initiative-put-patients-center-us-healthcare-system

Wellness. Wellness incentives and initiatives represent a tiny fraction of total spending by the U.S. healthcare system — likely in the low single digit percentages. Our system is known for its orientation around sick care, but what if reimbursement could be shifted dramatically towards prevention and wellbeing? A small absolute investment could be a big lever for longer-term health outcomes. The Singapore National Steps Challenge is a good example of providing modest financial incentives to encourage exercise. Could this concept be extended to healthy eating and other preventative measures?